Forecasting the Future

Lecture 5 - Management Science

Introduction

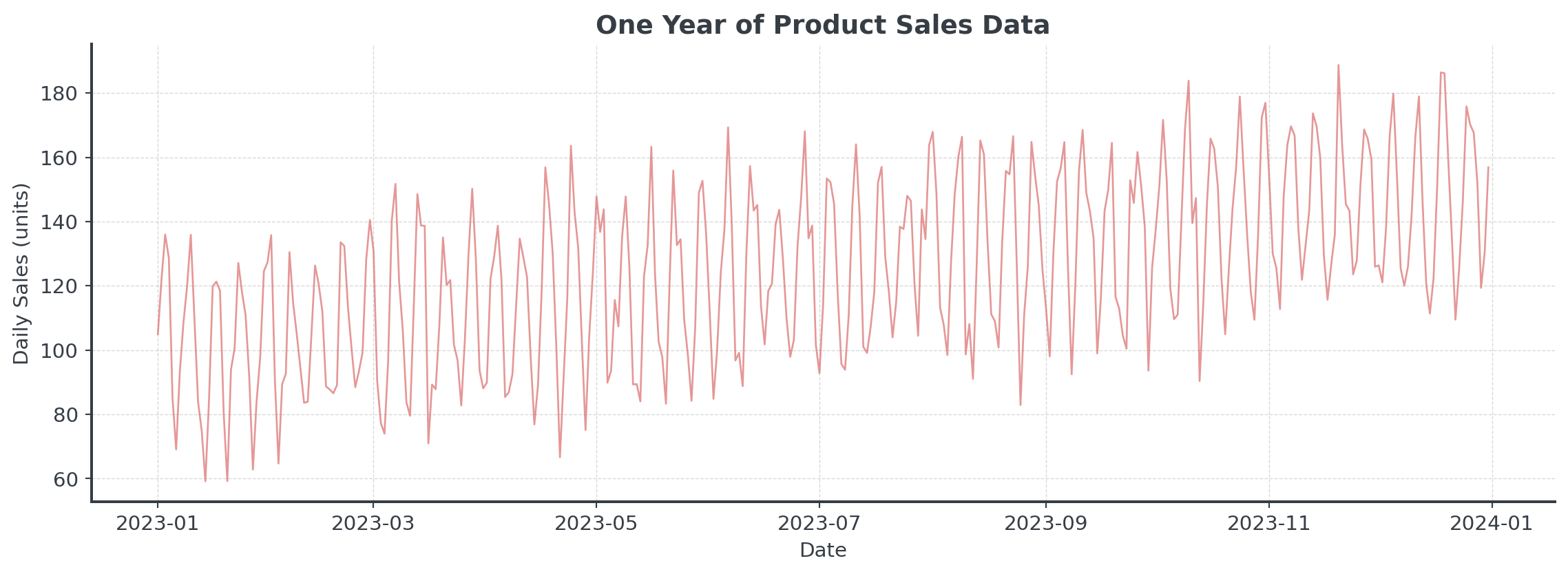

Client Briefing: MegaMart Retail Chain

. . .

Operations Director’s Crisis:

“Last Christmas, we ran out of PlayStation 5s but had 500 unsold fitness trackers. We lost €2M in missed sales and clearance losses. How do we predict what customers will actually buy?”

Business: The Unknown Future

Question: Why can’t we just order the same as last year?

- Market: New products, competition

- Seasonal Shifts: Weather, holidays, economic conditions

- Trend Changes: Changing preferences, new technologies

- Randomness: Viral TikToks, supply chain disruptions, pandemics

. . .

Reality: Large retailers process several thousand orders per hour. Each stockout basically means lost revenue + unhappy customers.

Core Concepts

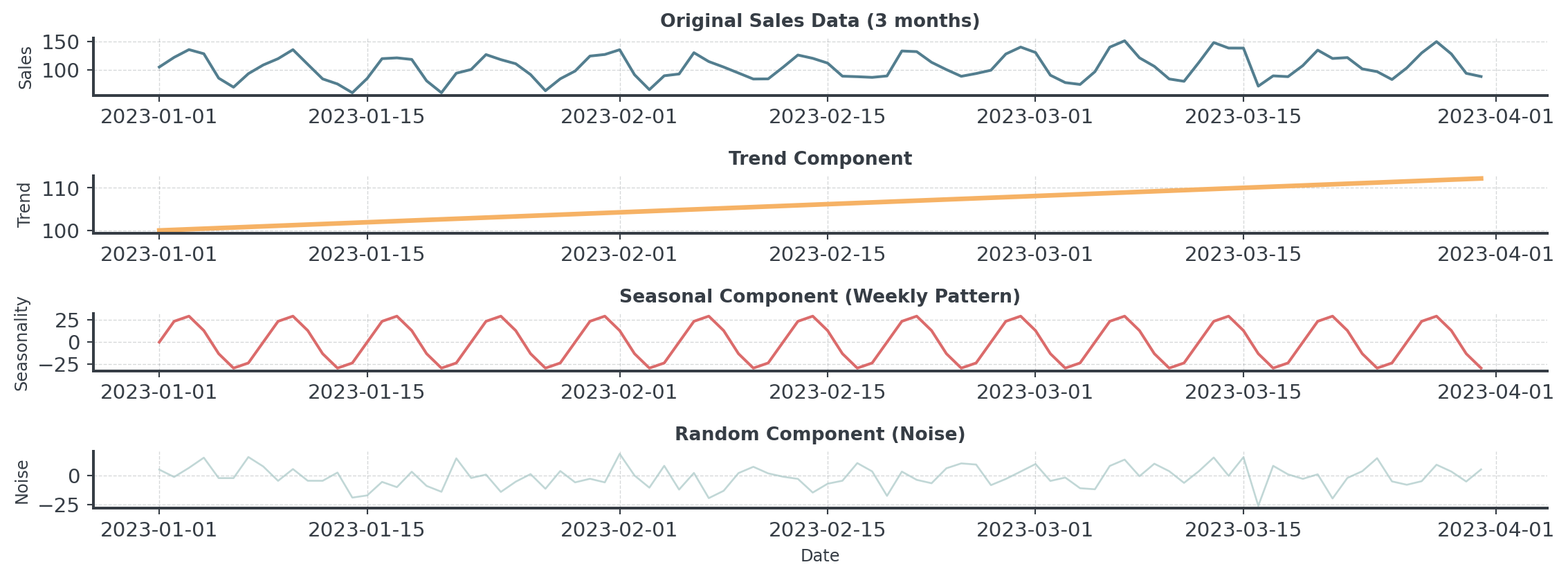

Decomposing Time Series

Time series can often be decomposed:

. . .

\[Y_t = T_t + S_t + R_t\]

. . .

Where:

- \(Y_t\) = Observed value at time t

- \(T_t\) = Trend component

- \(S_t\) = Seasonal component

- \(R_t\) = Random/Residual component

Additive vs Multiplicative Models

How do the components combine?

. . .

Additive Model \[Y_t = T_t + S_t + R_t\]

- Seasonal fluctuations are constant

- “We always sell 200 extra in December”

- Good: Stable, mature products

Multiplicative Model \[Y_t = T_t \times S_t \times R_t\]

- Seasonal fluctuations scale with trend

- “December sales are 40% higher”

- Good: Growing businesses

Visual Decomposition

. . .

Here: Sales = Trend + Seasonality + Random Noise

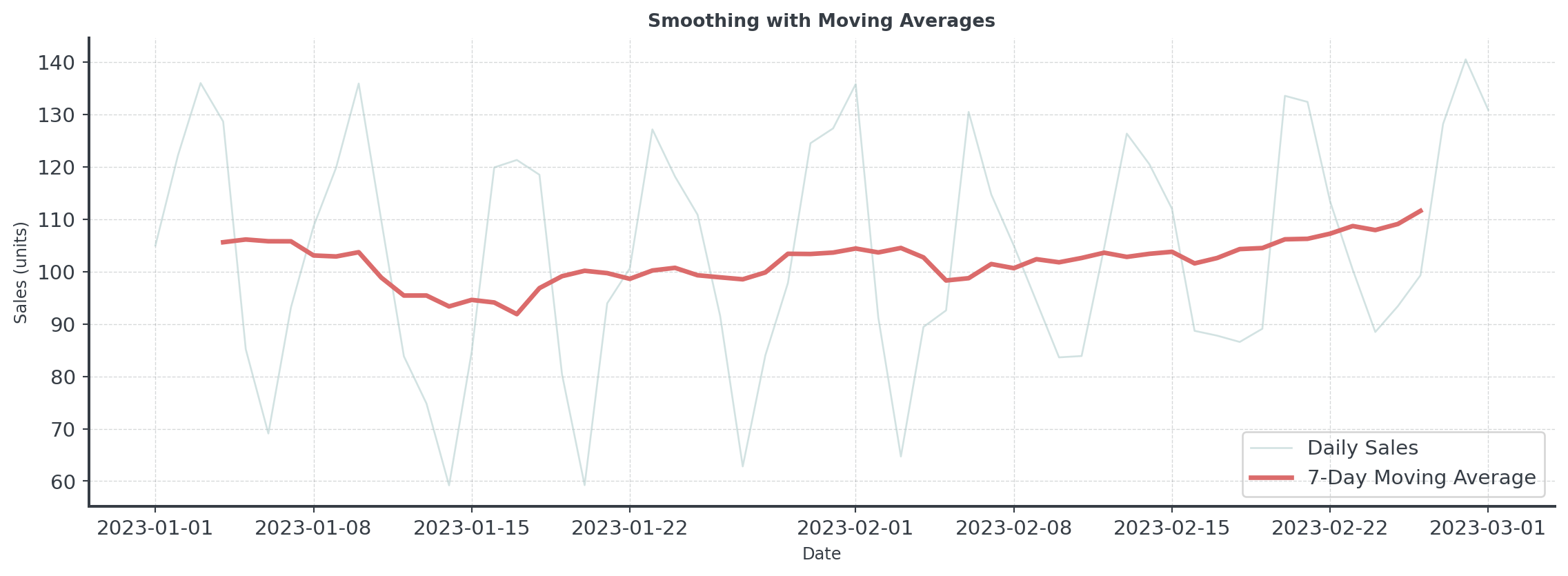

Moving Average

Question: How do we separate signal from noise?

. . .

Simple vs Weighted Averages

Which forecast would you trust more?

. . .

Simple Moving Average

- All days equally important

- We just take the average

- [14, 15, 16, 14, 15, 16, 17]

- Forecast: 15.3

Weighted Moving Average

- Recent days matter more

- Days closer are weighted more

- [0.05, 0.05, 0.1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.2, 0.3]

- Forecast: 15.9

. . .

Recent data often predicts the future better than old data!

Exponential Smoothing Methods

Simple Exponential Smoothing

Not too simple, not too complex

. . .

\[\text{Forecast}_{t+1} = \alpha \times \text{Actual}_t + (1-\alpha) \times \text{Forecast}_t\]

. . .

- α (alpha) = smoothing parameter (0 to 1)

- α = 0.9: Trust recent data (reactive)

- α = 0.1: Trust historical patterns (stable)

- α = 0.3: Balanced approach (common default)

. . .

Think of \(\alpha\) like: How much do you trust the latest data point?

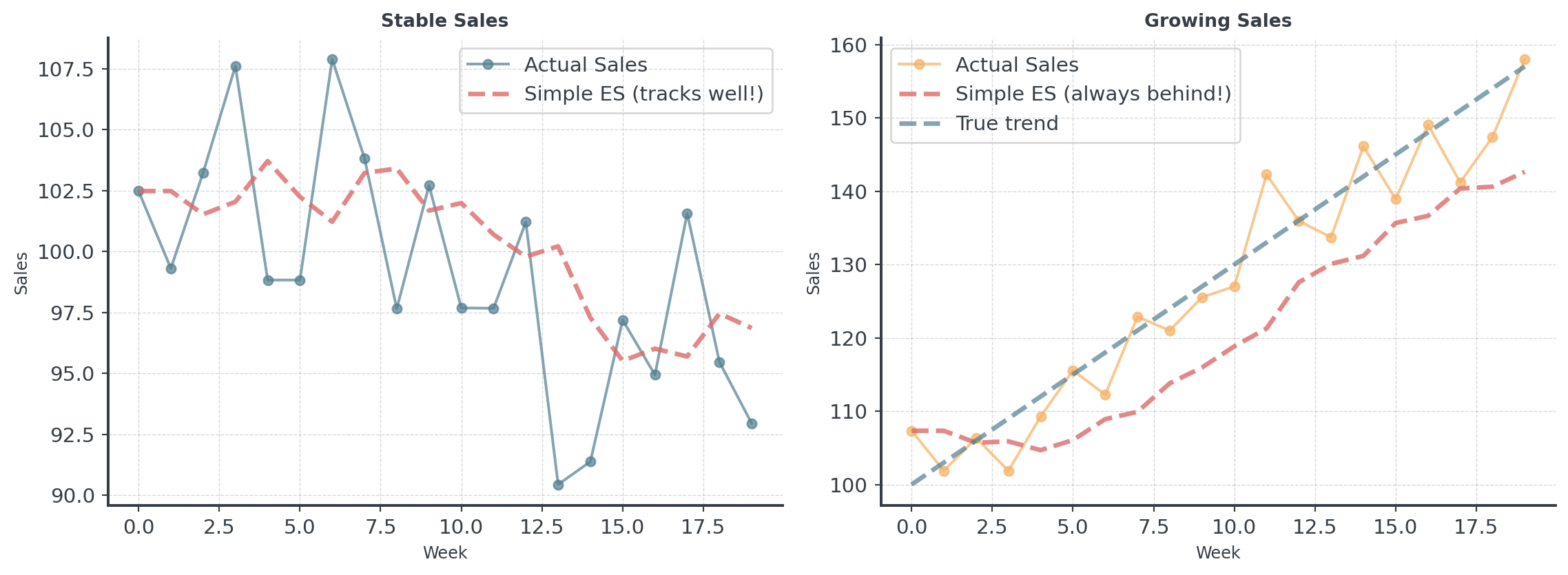

When Simple Smoothing Fails

Simple smoothing assumes the data is flat. What if it’s not?

Adding Trend

Holt’s Method: The Idea

Track TWO things separately: Level and Trend

- Level (L): Where are we right now? (like simple ES)

- Trend (b): How fast are we growing/declining per period?

- Forecast: Combine both: Level + (Trend × periods ahead)

. . .

Why This Works:

- Simple ES only tracks level (current position)

- Holt’s also tracks the slope (direction and speed)

. . .

Think of driving a car: Simple ES only knows your position. Holt’s also knows your speed!

Holt’s Method: The Math I

The formulas (simplified for intuition):

. . .

Level Equation: \[L_t = \alpha \times Y_t + (1-\alpha) \times (L_{t-1} + b_{t-1})\]

Trend Equation: \[b_t = \beta \times (L_t - L_{t-1}) + (1-\beta) \times b_{t-1}\]

Forecast Equation: \[\hat{Y}_{t+h} = L_t + h \times b_t\]

Holt’s Method: The Math II

In plain English

- Level: “Smooth current observation with previous forecast”

- Trend: “Smooth the change in level with our previous trend”

- Forecast: “Start at current, add trend for each period ahead”

. . .

Not too complicated, right?

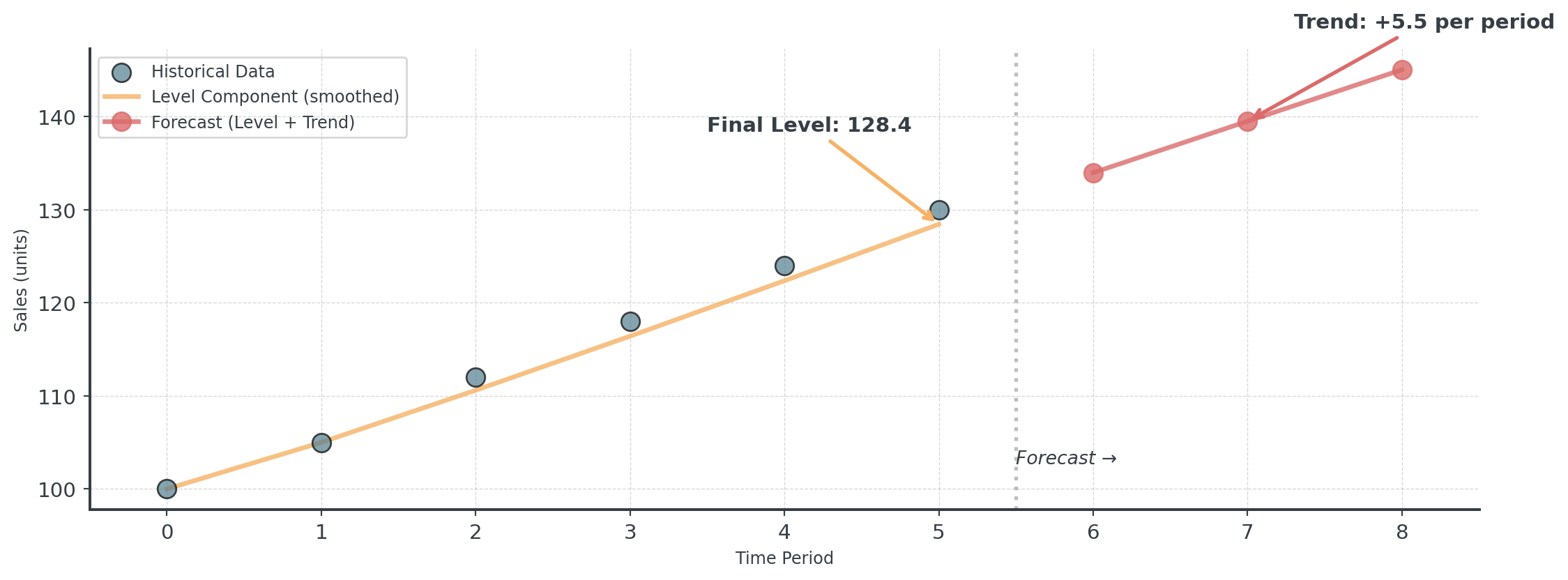

Step-by-Step I

Let’s walk through 6 periods manually to build intuition

# Sample data with clear upward trend

sales_data = np.array([100, 105, 112, 118, 124, 130])

# Parameters

alpha = 0.3 # Level smoothing

beta = 0.2 # Trend smoothing

# Initialize

level = sales_data[0] # Start at first observation

trend = sales_data[1] - sales_data[0] # Initial trend estimate

print(f"Period 1: Level={level:.1f}, Trend={trend:.1f}")

# Store level and trend history for visualization

level_history = [level]

trend_history = [trend]Period 1: Level=100.0, Trend=5.0Step-by-Step II

# Apply Holt's method for periods 2-6

for t in range(1, len(sales_data)):

# Update level

prev_level = level

level = alpha * sales_data[t] + (1 - alpha) * (prev_level + trend)

# Update trend

trend = beta * (level - prev_level) + (1 - beta) * trend

# Store for visualization

level_history.append(level)

trend_history.append(trend)

print(f"Period {t+1}: Sales={sales_data[t]}, Level={level:.1f}, Trend={trend:.1f}")Period 2: Sales=105, Level=105.0, Trend=5.0

Period 3: Sales=112, Level=110.6, Trend=5.1

Period 4: Sales=118, Level=116.4, Trend=5.3

Period 5: Sales=124, Level=122.4, Trend=5.4

Period 6: Sales=130, Level=128.4, Trend=5.5Step-by-Step III

# Forecast next 3 periods

print(f"\nForecasts:")

forecast_values = []

for h in range(1, 4):

forecast = level + h * trend

forecast_values.append(forecast)

print(f" Period {len(sales_data)+h}: {forecast:.1f} units")

Forecasts:

Period 7: 134.0 units

Period 8: 139.5 units

Period 9: 145.0 unitsHolt’s Method: Visual Comparison

Choosing Alpha and Beta

How do you pick the right smoothing parameters?

. . .

Alpha (Level Smoothing)

- High α (0.7-0.9): Responsive

- Use: Volatile markets

- Low α (0.1-0.3): Stable

- Use: Steady business

Beta (Trend Smoothing)

- High β (0.5-0.8): Quickly

- Use: Dynamic growth/decline

- Low β (0.1-0.3): Stable trend

- Use: Consistent growth

. . .

Best Practice: Let the algorithm optimize parameters automatically!

. . .

You can implement Holt’s method using Python’s statsmodels library!

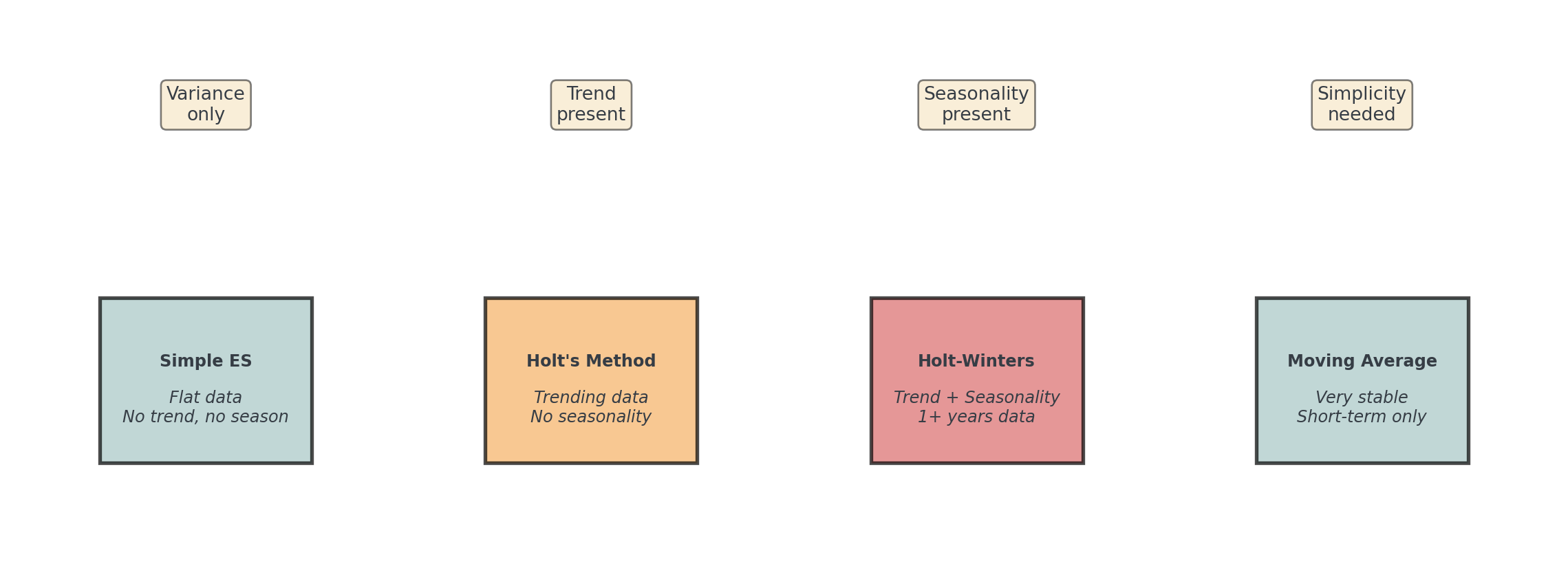

When to Use

Question: When should you use Holt’s method?

. . .

- Clear upward or downward trend

- No seasonal patterns

. . .

Question: When should you use NOT Holt’s method?

- Data is flat (use simple ES instead)

- Strong seasonality present

- Trend direction changes frequently

Adding Seasonality

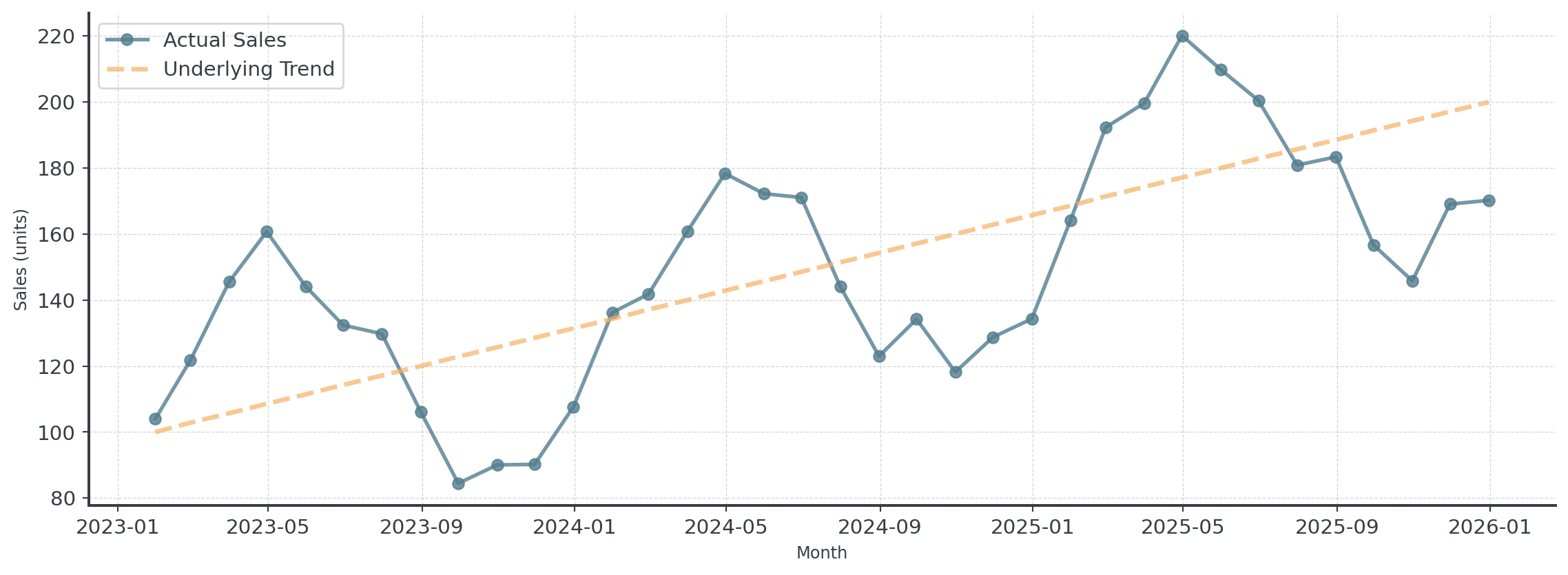

The Problem: Trend + Seasonality

What if your data has BOTH trend AND seasonality?

. . .

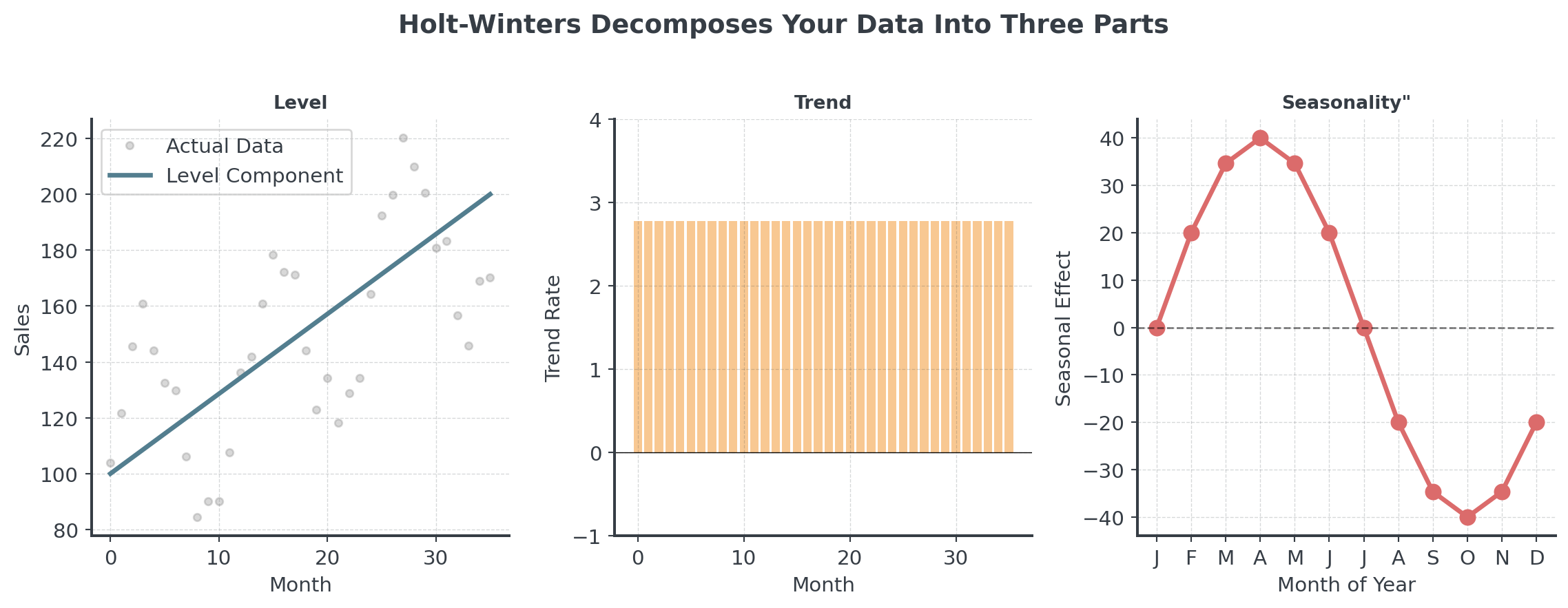

Holt-Winters: Three Components

Track THREE things separately: Level, Trend, AND Seasonality

- Level (L): Current baseline demand (deseasonalized)

- Trend (b): Growth rate per period

- Seasonal Indices (s): Multipliers for each season

Holt-Winters Visualized

Seasonality

How does seasonality combine with the level?

. . .

Additive Model \[Y_t = L_t + b_t + s_t\]

- Seasonal variation is constant

- “We sell +50 units every December”

- Pattern: ±constant amount

Multiplicative Model \[Y_t = L_t \times b_t \times s_t\]

- Seasonal variation scales with level

- “December is 1.5× normal sales”

- Pattern: ×percentage change

Holt-Winters: The Math I

The formulas (don’t panic - Python does this for you!)

. . .

Additive Model:

\[L_t = \alpha(Y_t - s_{t-m}) + (1-\alpha)(L_{t-1} + b_{t-1})\] \[b_t = \beta(L_t - L_{t-1}) + (1-\beta)b_{t-1}\] \[s_t = \gamma(Y_t - L_t) + (1-\gamma)s_{t-m}\] \[\hat{Y}_{t+h} = L_t + hb_t + s_{t+h-m}\]

Holt-Winters: The Math II

In plain English

- Level: Remove seasonality from observation, then smooth

- Trend: Same as Holt’s method

- Seasonal: Update the seasonal index for this period

- Forecast: Level + trend + seasonal adjustment

. . .

Parameters:

\(\alpha\) (level), \(\beta\) (trend), \(\gamma\) (seasonal), m (seasonal period length)

Holt-Winters: Intuition I

Understanding seasonal patterns with quarterly sales

. . .

Quarterly Sales Pattern:

- Q1: Low season (after holidays) → Factor: 0.85

- Q2: Spring pickup → Factor: 0.95

- Q3: Summer growth → Factor: 1.05

- Q4: Holiday peak! → Factor: 1.15

Holt-Winters: Intuition I

How Holt-Winters Works

- Deseasonalize the data (remove seasonal effect)

- Calculate trend from deseasonalized data

- Update seasonal indices based on actual vs. expected

- Forecast by combining level + trend + seasonal pattern

. . .

Q4 is typically 35% higher than Q1 in retail! Holt-Winters captures this automatically.

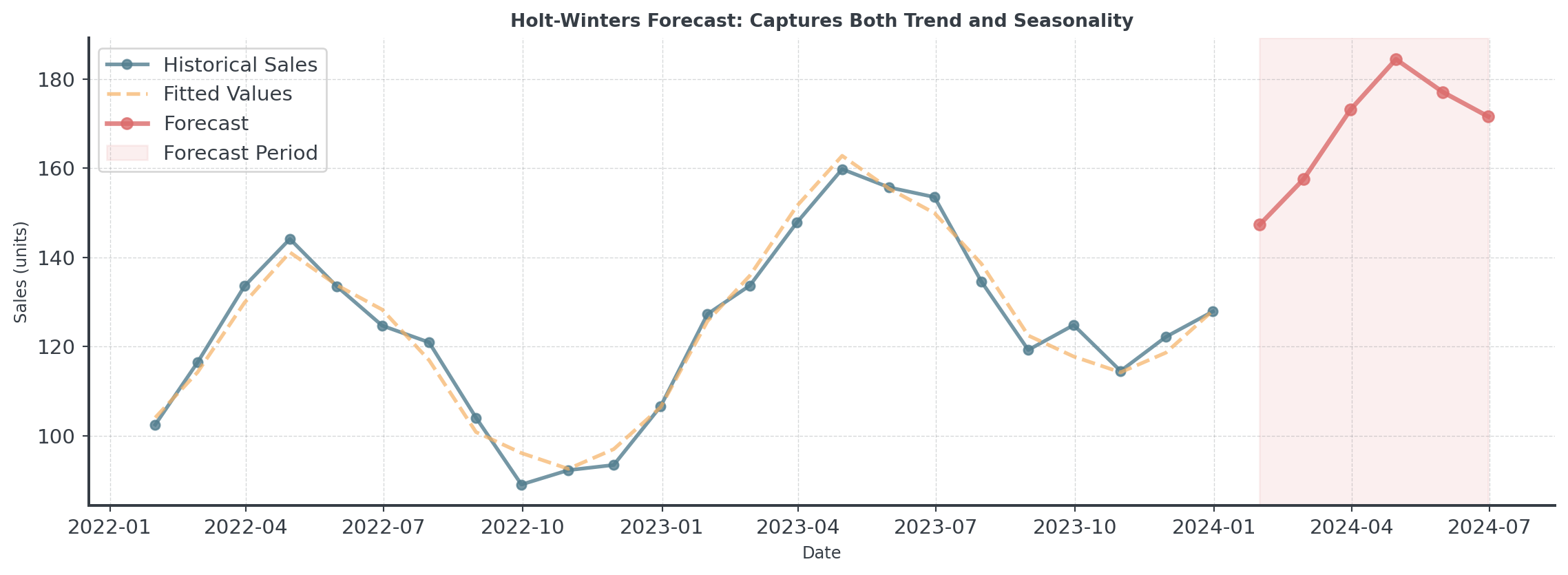

Holt-Winters: Visual

. . .

Notice how the forecast continues the seasonal pattern while following the trend!

When to Use Holt-Winters

Question: When should you use Holt-Winters method?

. . .

- Data with trend AND seasonality

- At least 1 full seasonal cycle (2 are better!)

- Regular, repeating patterns

. . .

Question: When should you AVOID Holt-Winters method?

. . .

- Irregular or changing seasonal patterns

- Flat data with no trend

- Seasonal pattern length unknown

Method Selection & Validation

Measuring Forecast Accuracy

How wrong were we?

. . .

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Average size of mistakes \[\text{MAE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} |Actual_i - Forecast_i|\]

. . .

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): Penalizes large errors more \[\text{RMSE} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (Actual_i - Forecast_i)^2}\]

Forecast Accuracy

Easy with Python

# Example: Compare two forecasting methods

actual = np.array([100, 105, 110, 108, 112])

forecast_a = np.array([98, 107, 109, 110, 111])

forecast_b = np.array([102, 103, 112, 106, 113])

mae_a = np.mean(np.abs(actual - forecast_a))

mae_b = np.mean(np.abs(actual - forecast_b))

print(f"Method A - MAE: {mae_a:.2f} units")

print(f"Method B - MAE: {mae_b:.2f} units")

print(f"\nBetter method: {'A' if mae_a < mae_b else 'B'}")Method A - MAE: 1.60 units

Method B - MAE: 1.80 units

Better method: AWhen to Use Which Method?

. . .

. . .

Start simple: Try moving average first as baseline, then add complexity only if needed!

The Real Cost of Being Wrong

Not all forecast errors are equal!

. . .

Example: Winter Coats

- Cost: €50, Selling Price: €150, Margin: €100

- Storage cost: €5/month

- Clearance markdown: 70% off

. . .

Question: What is your intuition here?

Under and Overforecasting

Sometimes it’s cheaper to overstock than to miss sales!

. . .

Underforecast by 100 units:

- Lost profit: 100 × €100

- €10,000

- Customer disappointment

- Competitor gains market share

Overforecast by 100 units:

- Storage: 100 × €5 × 3 months

- €1,500

- Clearance loss: 100 × €70

- €7,000

. . .

The “best” forecast depends on your business context.

Method Implementation

Your Python Practice Notebook

All the hands-on coding happens in the interactive tutorial!

. . .

- Working with dates in Pandas

- Implementing moving averages

- Building forecast functions

- Applying Holt’s method

- Using Holt-Winters

- Measuring accuracy

. . .

The notebook guides you step-by-step through Bean Counter’s seasonal demand forecasting challenge!

AI & Machine Learning Forecasting

The Promise of AI

Can machines predict better than classical methods?

What AI/ML brings to forecasting:

- Handle hundreds of variables simultaneously

- Detect complex non-linear patterns

- Learn from massive datasets

- Adapt automatically to changes

. . .

AI doesn’t replace human judgment, it augments it when you have enough data!

Common AI/ML Forecasting

Overview of popular techniques

. . .

Traditional ML:

- Random Forest: Ensemble of decision trees

- XGBoost: Gradient boosting (very popular)

- Support Vector Machines: Pattern recognition

Deep Learning:

- LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory): For sequences

- Prophet (Facebook): Automated forecasting

- Neural Networks: Complex patterns

. . .

More complex ≠ Better! Simple methods often win in forecasting.

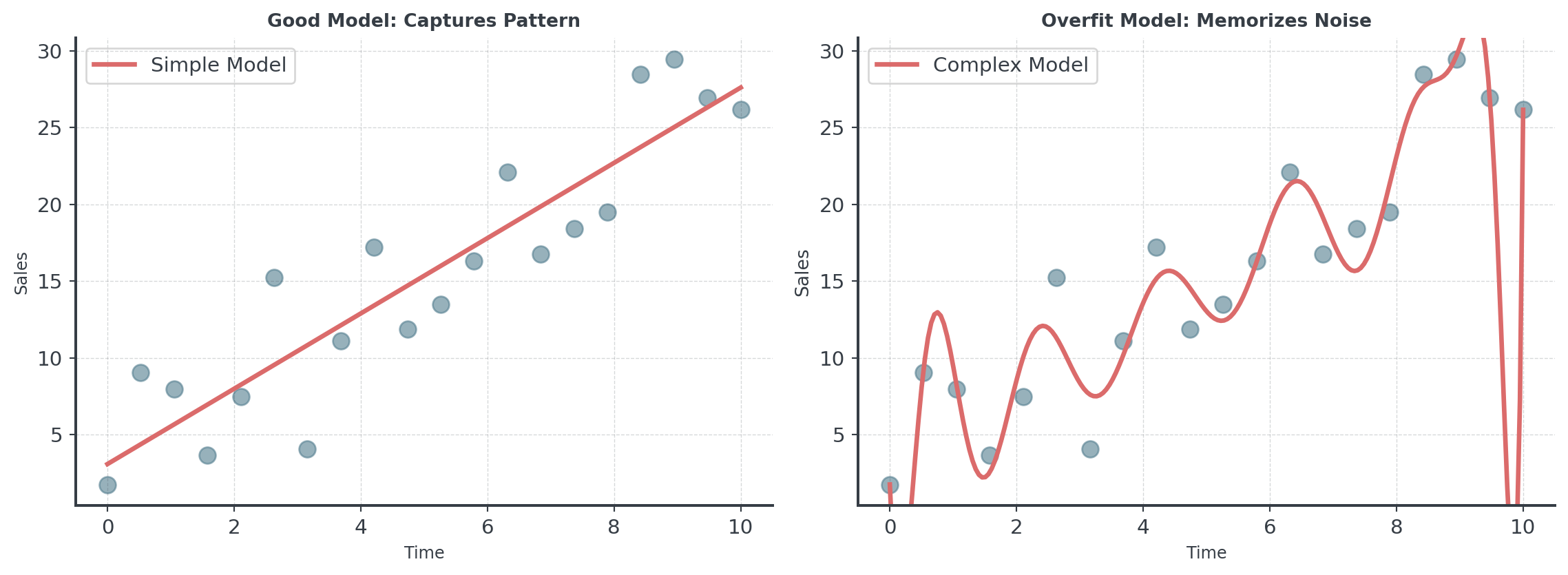

The Issue: Overfitting

Question: What happens when we train an AI on all our data and use it to predict… the same data?

. . .

Training vs Test Data

Never judge a complex model on the data it learned from!

- Training Data: Where the model learns patterns (70-80%)

- Validation Data: Where you tune hyperparameters (10-15%)

- Test Data: The “future”, only once for final evaluation (10-15%)

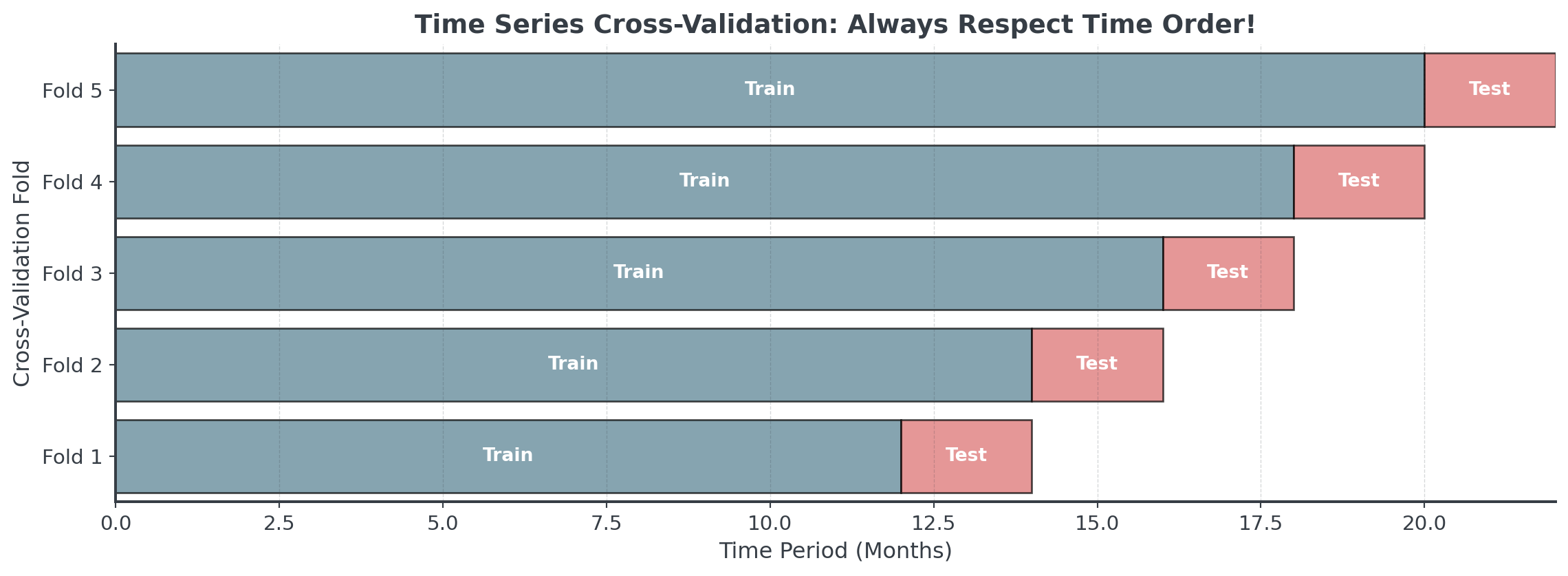

Data Leakage: The Silent Problem

When future information sneaks into your training data

. . .

- Target leakage

- Wrong: Including “total_sales” when predicting “monthly_sales”

- Right: Only use information available at prediction time

- Temporal leakage

- Wrong: Random split for time series (mixes past and future)

- Right: Always split chronologically

. . .

Data leakage can make a terrible model look amazing… until it fails in production!

Time Series Cross-Validation

. . .

Unlike regular cross-validation, we NEVER use future data to predict the past!

When to Use AI/ML Forecasting I

Use AI when you have:

. . .

- Sufficient historical data (2+ years)

- Rich feature data (weather, promotions, events)

- Non-linear patterns

- Resources for training/maintenance

. . .

Examples:

- Large retailers (Amazon, Walmart)

- Demand forecasting with many variables

When to Use AI/ML Forecasting II

Don’t use AI when you have:

. . .

- Limited historical data

- High noise, low signal

- Need explainable forecasts

- Limited expertise

. . .

Examples:

- New products (no history)

- Regulatory environments

Advanced Topics

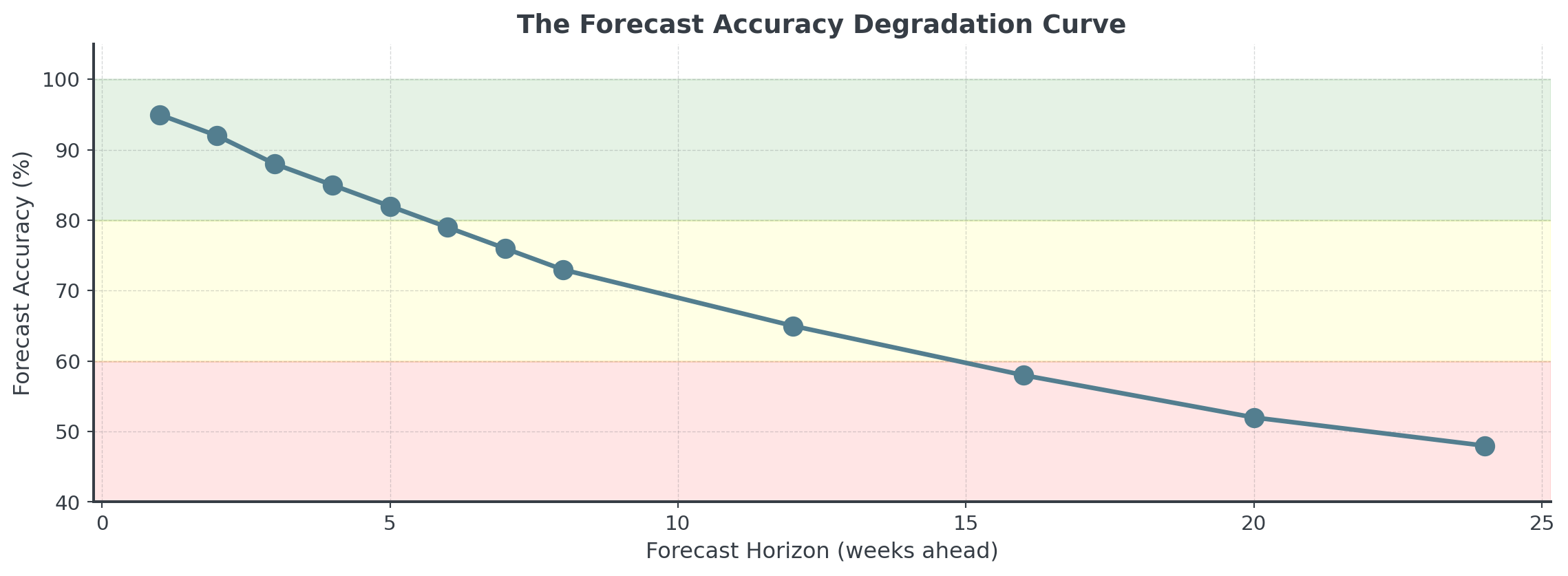

Forecast Horizons

How far into the future can we predict?

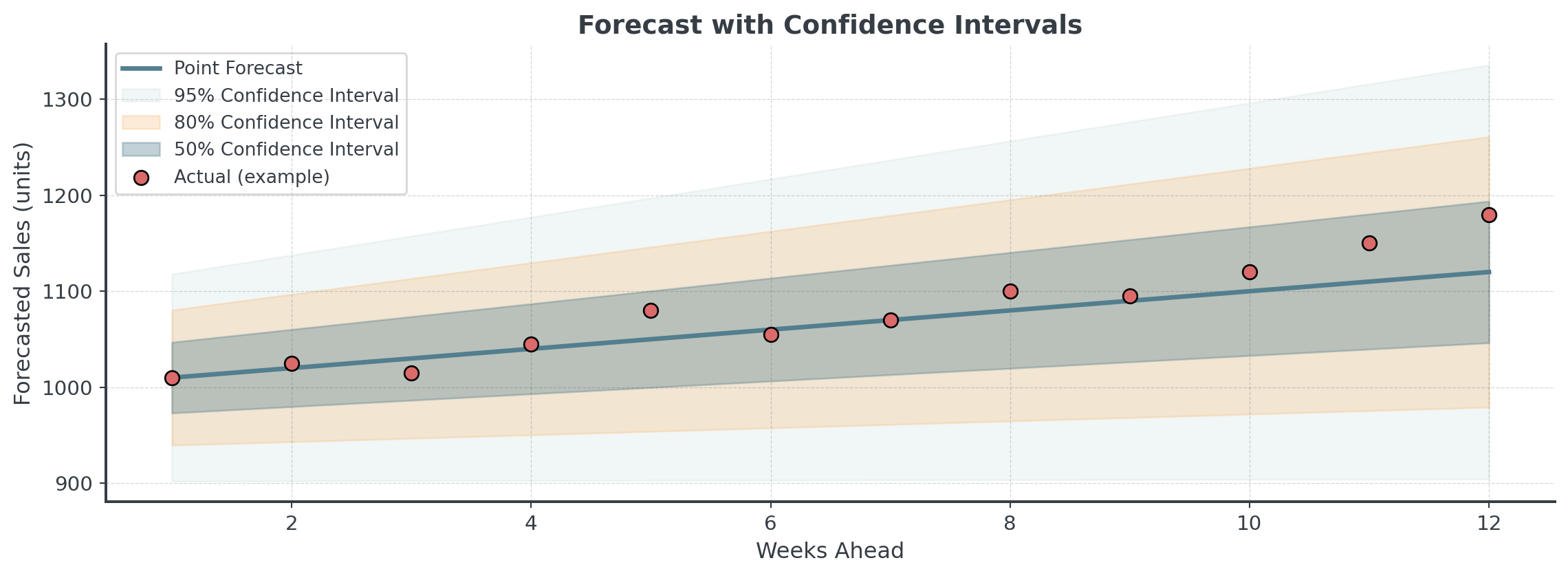

Confidence Intervals

A forecast without confidence intervals is incomplete!

Forecast Combination

Why choose one method when you can combine several?

. . .

# Example: Combining multiple forecasts

ma_forecast = 120 # Moving average prediction

exp_forecast = 125 # Exponential smoothing prediction

seasonal_forecast = 135 # Seasonal model prediction

# Simple average (equal weights)

simple_combo = (ma_forecast + exp_forecast + seasonal_forecast) / 3

print(f"Simple combination: {simple_combo:.0f} units")

# Weighted average (based on historical accuracy)

weights = [0.3, 0.5, 0.2] # Exp smoothing was most accurate historically

weighted_combo = (ma_forecast * weights[0] +

exp_forecast * weights[1] +

seasonal_forecast * weights[2])

print(f"Weighted combination: {weighted_combo:.0f} units")Simple combination: 127 units

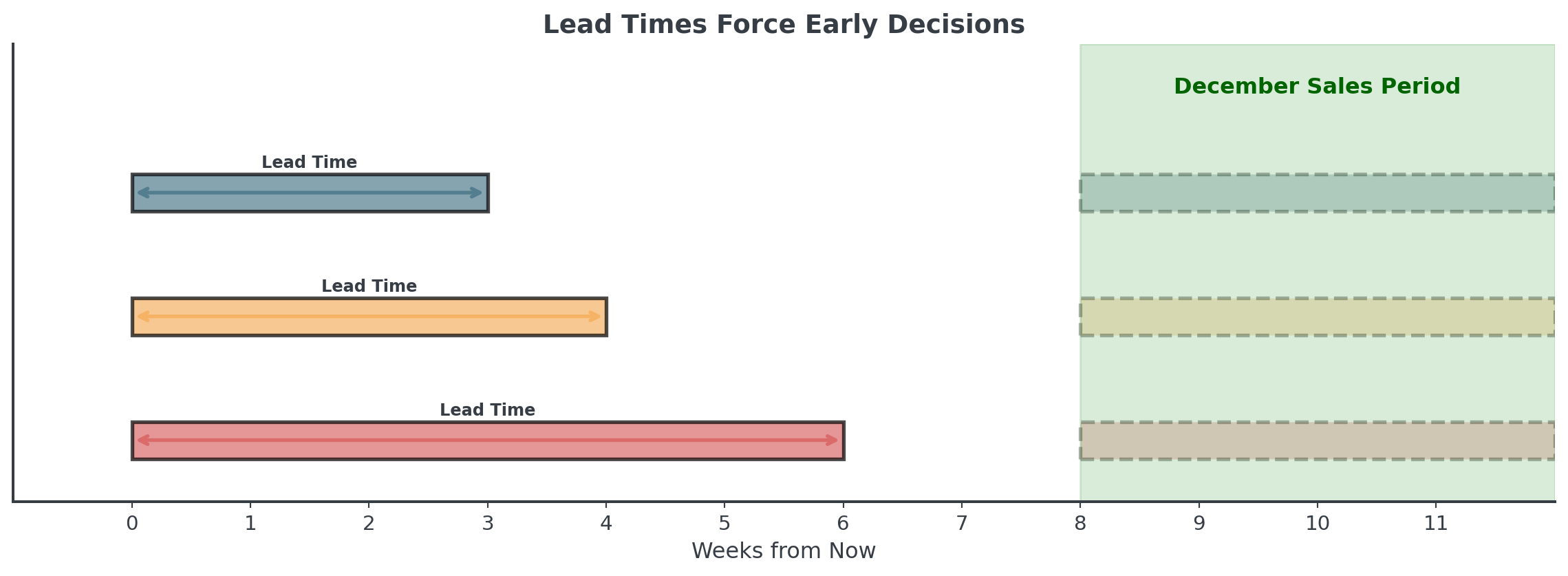

Weighted combination: 126 unitsLead Times and Safety Stock

. . .

Long lead times = Forecasting further out = Less accuracy = More safety stock!

Safety Stock Calculation

How much buffer do you need?

. . .

# Safety stock formula

import scipy.stats as stats

avg_weekly_demand = 300; std_weekly_demand = 40; lead_time_weeks = 3

service_level = 0.95 # Want 95% availability

# Z-score for 95% service level

z_score = stats.norm.ppf(service_level)

# Safety stock calculation

safety_stock = z_score * std_weekly_demand * np.sqrt(lead_time_weeks)

reorder_point = (avg_weekly_demand * lead_time_weeks) + safety_stock

print(f"Average demand during lead time: {avg_weekly_demand * lead_time_weeks} units")

print(f"Safety stock needed: {safety_stock:.0f} units")

print(f"Reorder point: {reorder_point:.0f} units")Average demand during lead time: 900 units

Safety stock needed: 114 units

Reorder point: 1014 unitsToday’s Tasks

Today

Hour 2: This Lecture

- Patterns & decomposition

- Simple ES, Holt’s, Holt-Winters

- Method selection

- Practical pandas

Hour 3: Notebook

- Bean Counter CEO

- Daily and weekly aggregation

- Implement methods

- Compare accuracy

Hour 4: Competition

- MegaMart challenge

- 3 real products

- 4-week forecast

- €10K per error unit!

The Competition Challenge

“The Christmas Predictor”

. . .

- Analyze 2 years of weekly sales for 3 products

- Identify patterns (trend, seasonality, volatility)

- Forecast 4 December weeks for each product

- Minimize Mean Absolute Error across all 12 predictions

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

The Rules of Forecasting

- Always plot first - Your eyes catch patterns algorithms miss

- Start simple - Complexity is not your friend

- Recent matters more - Weight recent data higher

- Match method to pattern - Trend? Seasonality? Match!

- Validate on holdout - Never test on training data

- Add confidence intervals - Uncertainty is information

- Consider business context - Cost of errors matters

Final Thought

Forecasting is both art and science

. . .

The Science:

- Statistical methods

- AI based forecasting

- Error metrics (MAE, RMSE)

- Confidence intervals

- Systematic validation

The Art:

- Choosing the right method

- Balancing complexity vs simplicity

- Interpreting context

- Communicating uncertainty

. . .

Make better decisions, not perfect predictions!

Break!

Take 20 minutes, then we start the practice notebook

Next up: You’ll become Bean Counter’s forecasting expert, preparing for seasonal demand!

Then: The MegaMart Christmas Challenge!